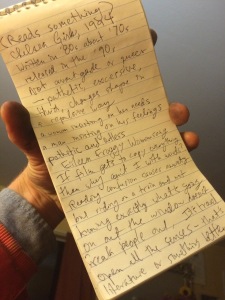

My friend and I smoked pot and then rode bikes down to the state school student union to see the poet Eileen Myles. After inquiring later what kind of weed it was I was told it was called Cinex.

I first learned of Eileen Myles from another friend who read to me from her novel Inferno at two stages of our friendship, the first occurring mostly on the floor of her apartment and the second being in a rental car driving over the Sierra Nevada out of Granada. She lives in Oregon now as well, but couldn’t come that night and asked me to take notes so I did.

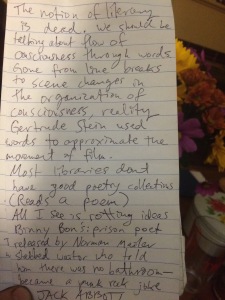

Ms. Myles prefaced her talk as “a wandering” in that she was not simply going to just talk, read, or take questions—she would say whatever needed to be said, it turned out, whenever it needed to be in said, with sentences constantly needing to be said before the previous one was finished. Every word as a consequence wielded an urgency generally absent from most discourse apart from quiz shows.

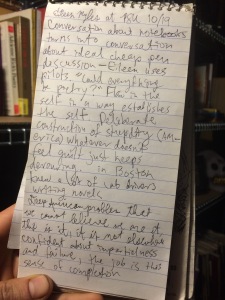

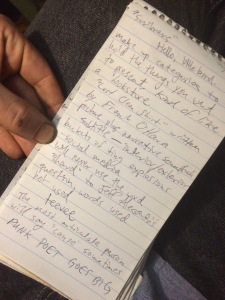

She began by taking our her notebook, which fumbled for in her bag. There were other moments of silence: when Ms. Myles went to the back of the room to retrieve her water bottle, or when she threw a book against the wall after accidentally dropping it, again fumbling in her bag. I guess throwing a book against the wall doesn’t quite count as a moment of silence as much as a moment of not saying things into the microphone. A paperback book being thrown has a combination of a flapping swoosh sound turning into a not-quite-solid thwack, more fluttery as all pages don’t really hit at once, ending of course with a thump and similarly fluttery settle. A moment of not talking in a room full of people is fairly indescribable and quite beautiful when one detaches it from the feelings of discomfort we’ve been trained to associate with it in these United States.

The throw of the book signifies much and deserves some more attention. By choosing to follow the potentially awkward “accident” of mishandling an object in front of a large group of people with an exaggerated repetition of that same supposed mistake, Ms. Myles recapitulates the theme of her talk of overcoming the fear of inferiority in art and the American identity.

By treating a notebook of fragments at the same level as a big-house-published book of poems and reading from it during a tour for the big-house-published book reduces the commodification of the writing: the book of poems or the reissue from Harper Collins are not the end, the inevitable proof of status, integrity, success, they are just another form of presenting a poet’s words to an audience. As it turns out, such a form becomes the means to reading to more people and the freedom to create better circumstances for the creation of more poetry, or a means to the more accurate end of writing words into notebooks. Any writer who prides themself on how many words they have bound in Costcos across the world instead of how many notebooks they fill with experiments, failures and honesty is more of a failure than all of the unpublished poets poisoned by their unrequited relationship with commodification of truth.

The fact of the very reading became a theme as well, that Ms. Myles was no longer an outsider artist but now a mainstream commodity. She was reading at the iconic local bookstore. Her out-of-print 1994 Black Sparrow novel Chelsea Girls was being reissued by Harper Collins. She was speaking to a packed room at the student union of the state school. She treats her success, however, as entirely arbitrary. There is suddenly a market for lesbian poetry. She has been canonized by commerce. The supposed literary world has dubbed her intentional artlessness to be art. The literary world has welcomed her decades into the death of the literary. She’s a punk singer who gets signed to a major label at the age of 65. Ms. Myles is not at risk of selling out because it’s been long established that nothing can stop her from doing exactly what she wants to do. She taught herself to write a novel, she said, by writing the only kind of novel she could write, and then knew how to write a novel, that novel being Chelsea Girls. Reissued this year by Harper Collins.

Leafly.com writes of Cinex it has “clear-headed and uplifting” effects. Not only that, but it’s “perfect for building a positive mindset and stimulating creative energy.” Also: It alleves pain AND DEPRESSION!

This could explain why Ms. Myles’ run-on aphorisms sounded like gospel truth, perfectly at play with my own intellectual preoccupations. Inferno was important for me in capturing my fears and discouragements at the time, the feelings of worthlessness and insanity that accompany writing in obscurity, essentially identifying as something you are failing at—in other words the subject matter of the great struggling writer myth we’re stuck with until we cross an imaginary line that Ms. Myles admits both to have crossed and to believe does not really exist.

What I’m getting at is that Ms. Myles purposefully rambled truth at us for an hour—there’s no doubt about that—but the 60/40 sativa-dominant grass followed by a bike ride accompanied by the new Miley Cyrus album just made that truth hit that much more saliently. Like waves rippling over the rows of the audience, inundating us with assurance that in a country dedicated to the “deliberate construction of stupidity,” anybody who resists will be made to feel crazy, convinced that the imaginary lines that separate all the halves, the haves from the haven’ts, are real and inevitable.

As allbud.com describes, “after just a few tokes of this abstract strain, you will be uplifted into a euphoric high that takes you into a cognitive wonderland.” For whatever reason, that description is paired with a 3.5 star rating. Out of 5! Whoever didn’t give this grass 5 stars didnt go see Eileen Myles read after they smoked it.

The problem with my field notes is that they’re not full of accurate quotes, and they’re not fully comprehensible on their own without some context. So I shall leave you with a paraphrase of the train analogy Ms. Myles employed to confront the idea that a reader cannot be confused in the reading experience. Incompleteness and ambiguity causes anxiety, a reader cannot go along with worda if their meaning is not perfectly clear. Writing combines things that the reader knows with what they dont, and you cant expect them to keep going if they dont get all the particulars. Yet someone on a train looks out the window and sees things that they know and things they dont and people dont freak out. “It’s travel,” she concluded. Being comfortable in the not knowing and flowing with it. “Open all the senses—that’s literature, or something better.”

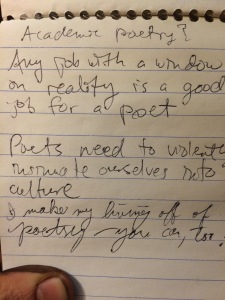

In response to someone asking if there’s profit in poetry, Ms. Myles found herself completing a thought that ultimately she was able to make a living at it. Smirking as she realized time was up as she said it she swung her arm around to gesture at the audience as though suddenly starring in an infomercial letting the lost know there’s a way out: “I make my living off of poetry—so can you!”

Two nights after the reading, I smoked more cinex at the house and transcribed these notes. Because my computer sucks I ended up writing most of this on the phone while listening to NPR. One more time for good meaure:

I the you